In many places around the world, the impacts of climate change are worsening people’s existing vulnerabilities, destabilizing communities and increasing the risk of certain diseases. This is particularly true in South Sudan, where Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams are running a pilot project looking at the effectiveness of a new malaria anticipation model.

In addition to multiple crises, including conflict and food insecurity, people in South Sudan have been affected by recurrent floods which, in certain regions, have reached unprecedented and catastrophic levels in recent years. The consequences of this phenomenon are disastrous: destruction of crops and livestock, forced displacement, malnutrition crises, contamination of drinking water and the spread of infectious diseases, including malaria.

“Land that was once arable is gradually being transformed into swampland, not seasonally as before, but permanently,” says Léo Lysandre Tremblay, lead for MSF’s Humanitarian Action on Climate and Environment unit, based in Canada. “These wetlands are incubators for the larvae of Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit malaria.”

USING CLIMATE DATA TO ANTICIPATE MALARIA PEAKS

In 2021, MSF launched the Malaria Anticipation Project. It aims to develop a warning tool that will enable MSF teams to take early action to improve planning, allocate resources and establish priorities.

nets to help prevent malaria. South Sudan, 2023. © MSF/Verity Kowal

“The early warning system is based on predictive models, which, in turn, draw on data on malaria and climatic indicators such as rainfall, temperature, humidity, wind speed and vegetation health,” says Tremblay. “This allows us to bring together a wealth of information and see how certain weather events, such as flooding, can impact malaria transmission.”

The model’s forecasts will support MSF’s work on four main factors for anticipating epidemics: prevention, healthcare services capacity, community involvement and advocacy.

In 2022, the World Health Organization estimated there were 249 million cases of malaria in 85 countries where the disease is considered endemic.

The incidence of malaria – which causes hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths every year, particularly among young children— is rising steadily while the affected geographic area is growing larger.

“As large-scale flooding becomes a new normal, we need to be better prepared,” says Michael Lawson, humanitarian affairs officer with MSF. “Better forecasts and more information are crucial in trying to know when and where to expect flooding and to invest in mitigation measures in advance.”

CONCLUSIVE TRIALS LEAD TO LARGE-SCALE PROTOTYPE

The project is currently being tested in Lankien, Jonglei State, South Sudan, where MSF supports several health facilities. It adds to various preventive activities already being implemented in the region, such as insecticide spraying, prevention using medication, mosquito net distribution and awareness programs.

“The model works quite well, de- spite data constraints due, among other things, to people and community movements,” says Tremblay. “It remains conclusive enough for us to develop a prototype on a larger scale.”

A second phase of the project will evaluate this prototype in southern South Sudan, a region hit hard by flooding in recent years and where MSF supports several projects.

Once these stages are complete, teams will focus on assessing the model’s potential impact and share findings with others, including the Ministry of Health. The aim remains to work together to plan medical activities and mobilize the resources needed to respond more effectively to the health threats of malaria, which impact not only international health but how we adapt our medical humanitarian work to the impacts of climate change.

Families affected by recurrent malaria – Nya Thor’s story

In Jonglei state, South Sudan, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams rush four critically ill patients by ambulance boat to the MSF hospital in the town of Old Fangak. Among them is Nya Sibet Mar, who holds her two-year-old daughter, Nya Thor, who is suffering from severe malaria.

It is the second time Nya Thor has malaria. According to her mother, more and more people have become sick with the disease since the heavy flooding, which started in 2019.

“Two years ago, our house was completely flooded, so we had to look for another place,” says Nya Sibet Mar. “We arrived in Toch, but because there is more water than before, we live surrounded by mosquitoes. We see a lot of malaria cases now compared to before the floods.”

In the hospital, MSF teams see both uncomplicated and severe malaria cases. Staff provide anti-malaria drugs, as well as treat complications such as severe vomiting, high fever, convulsions, pneumonia, anemia and malnutrition.

As Nya Siber Mar reaches the MSF hospital with her daughter, Nya Thor is experiencing complications and is admitted to the pediatric ward. MSF staff provide her treatment for both malaria and malnutrition.

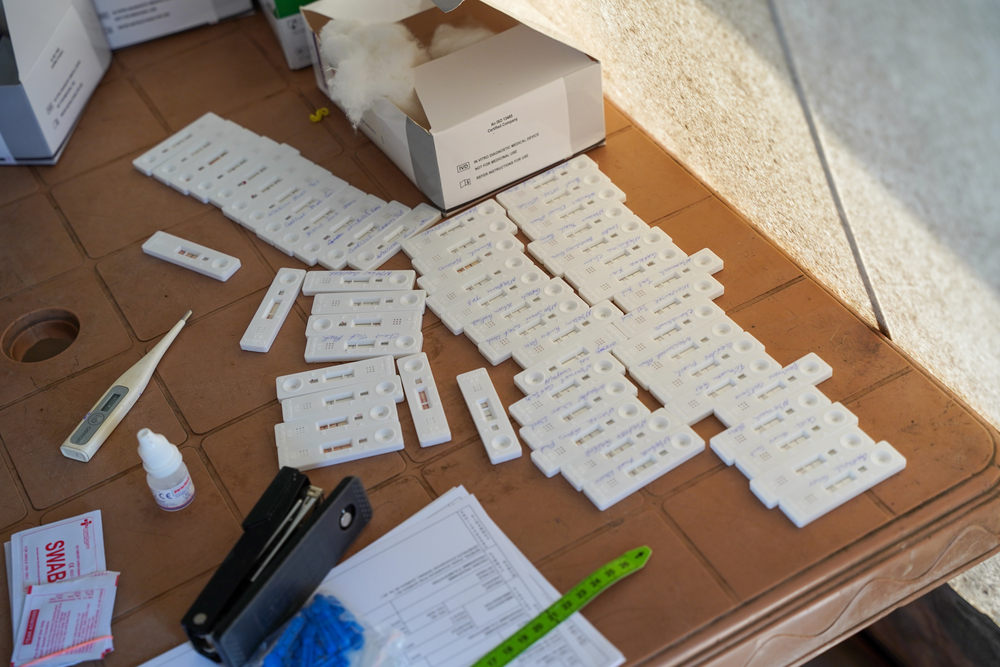

After three days at the hospital, Nya Thor and her mother are brought back to their village by MSF’s ambulance boat. That day, the MSF outreach team conducts malaria screening in the village: out of the 56 tests, 42 are positive.

Over the past few years, South Sudan has experienced severe flooding. Some regions now lie under vast expanses of stagnant water, an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes. This often leads to an explosion in malaria cases. Between July and September 2022, MSF teams treated 81,000 people for malaria in Ulang and Fangak regions

Fangak. South Sudan, 2023. © Manon Massiat/MSF