MSF WORKING TO ANTICIPATE PEOPLE’S MEDICAL NEEDS

The year 2023 was the hottest in recorded history. Driven by human-caused climate change, these record-breaking highs were also boosted by the natural El Niño phenomenon. What’s more, experts are predicting that 2024 will likely be even hotter, as El Niño conditions continue into the early part of the year. But what does this mean – and why do humanitarian organizations like Doctors Without Borders/ Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) care?

“The changing climate matters a great deal,” says Alexandra Malm, MSF strategic communications advisor for planetary health. “It has major health consequences and aggravates humanitarian situations. Experts project this will worsen as the planet heats up. People in already vulnerable circumstances around the world are the most affected – many of whom are the communities MSF works with.”

MSF RESPONDING TO ACUTE AND RECURRING CLIMATE-RELATED EMERGENCIES

MSF teams around the world are responding to the health consequences of soaring temperatures, changing seasonal weather patterns and extreme weather events on MSF teams around the world are responding to the health consequences of soaring temperatures, changing seasonal weather patterns and extreme weather events on sive flooding in South Sudan and a multi-year drought that has driven millions of people to the brink of starvation across the Horn of Africa. In Somalia, MSF has been responding to recurring humanitarian health emergencies. Climate change has locked the country in a spiral of droughts and floods, increasing the vulnerability of people in communities heavily affected by armed conflict. The most recent drought stretched for three years and was the driver for more than 58 per cent of displacement increasing the vulnerability of people in communities heavily affected by armed conflict. The most recent drought stretched for three years and was the driver for more than 58 per cent of displacement in the country in September 2023, according to the UN.

In late 2023, El Niño caused heavy rains and severe flooding to hit the Horn of Africa. Since October, parts of Somalia have been submerged. In the city of Baidoa alone, severe flooding has displaced more than 230,000 people, including families who were already living in informal displacement sites. Roads, bridges and buildings, including health facilities, have been damaged or destroyed, further cutting people off from medical care.

“These heavy rains have had a major impact on the maternity and neonate [wards]… All the activities stopped in the delivery, inpatient department and postnatal sections,” says Khadija Adan Ibrahim, a Ministry of Health nurse working in the MSF-supported Bay Regional hospital in Baidoa.

Floodwaters also contaminate water sources and contribute to poor sanitation, increasing the spread of waterborne diseases like cholera. A climate-sensitive disease, MSF teams were already seeing and responding to high levels of cholera in Somalia and across the Horn of Africa prior to the flooding.

What are El Niño and La Niña?

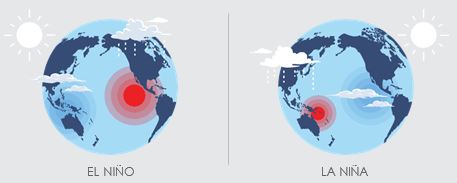

El Niño is known as the ‘warm phase’ of a cyclical weather pattern in the tropical Pacific Ocean, where normal east-west winds weaken or reverse. This causes sun-warmed water to collect in the central and east Pacific, which in turn releases hot and humid air into the atmosphere.

In May 2023, El Niño conditions were declared after nearly three years of La Niña, or the ‘cold phase’ of this same weather pattern. During La Niña, normal east-west winds become even stronger, pushing warm surface water further west and pulling cold ocean water up in the eastern Pacific.

Both El Niño and La Niña can cause dramatic changes in rainfall patterns and temperatures globally. Their exact relationship with climate change is still unknown but their impacts are expected to become more severe as global temperatures rise.

moderate and severe malnutrition in Soavina health centre. Madagascar regularly experiences extreme weather events.

Cyclones have worsened health problems for many vulnerable communities and exacerbated the already dire food

security situation. Madagascar, 2023.

© MSF/Mitsi Persani

Preparing for climate change in South Sudan

In a parched landscape, a Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) tractor towing a wooden canoe approaches a small village in Dentiuk in South Sudan’s Upper Nile state. “Are you sure we are in the right place?” asks the driver.

“It might not look like it, but when the rains come, this whole area is seriously hit by flooding and the only way to get around is by boat,” says Jorge, MSF’s logistics team leader.

Communities in South Sudan have long been affected by severe flood- ing, but the past few years have brought unprecedented floods, exac- erbated by climate change. El Niño-induced heavy rains around Lake Victoria and flooding are expected to continue to uproot people from their homes, destroy crops, drown cattle and damage infrastructure.

Against this backdrop, MSF teams have been working with communities to help prepare for the rainy season, while helping ensure they can still access healthcare. This includes delivering canoes to communities like the one in Dentiku to help transport sick people and expectant mothers. We are also training key members of remote communities in medical skills, from basic first aid to advanced care.

“We are training traditional birth attendants to give them extra skills to support expectant mothers as they rush them to the nearest health facili- ty,” says Dinatu, MSF’s lead midwife in Malakal.

At the same time, MSF teams have been positioning medical supplies throughout the country to help treat and prevent outbreaks of malaria and waterborne diseases like cholera. We are also working alongside vari- ous partners to enhance our flood prediction expertise in South Sudan.

to support the community in transporting sick people to hospital when it floods. South Sudan, 2023. © Paul Odongo/MSF

USING FORECASTS TO ANTICIPATE PEOPLE’S GREATEST MEDICAL NEEDS

Advanced warning and more information on changing seasonal patterns – whether or not induced by El Niño or La Niña – are crucial to help MSF prepare for and respond to emergencies around the world.

In Canada, MSF hosts the Humanitarian Action on Climate and Environment (HACE) initiative, which draws on publicly available resources and the conditions that are reported by MSF staff in several countries where we work, including South Sudan, Madagascar and Somalia. This is being done to develop simple forecasts to help our teams anticipate when and where people’s greatest needs will be.

But this type of information needs to be collected and analyzed at a much larger scale than what MSF can produce on our own. Governments, space agencies, universities and other researchers can help provide data and produce better models that can be shared with humanitarian actors and other responders.